The Duck Hunt: The search for three war heroes on the Greenland ice cap.

Crash Site

Southeast Greenland

Date Missing

November 29, 1942

On Board

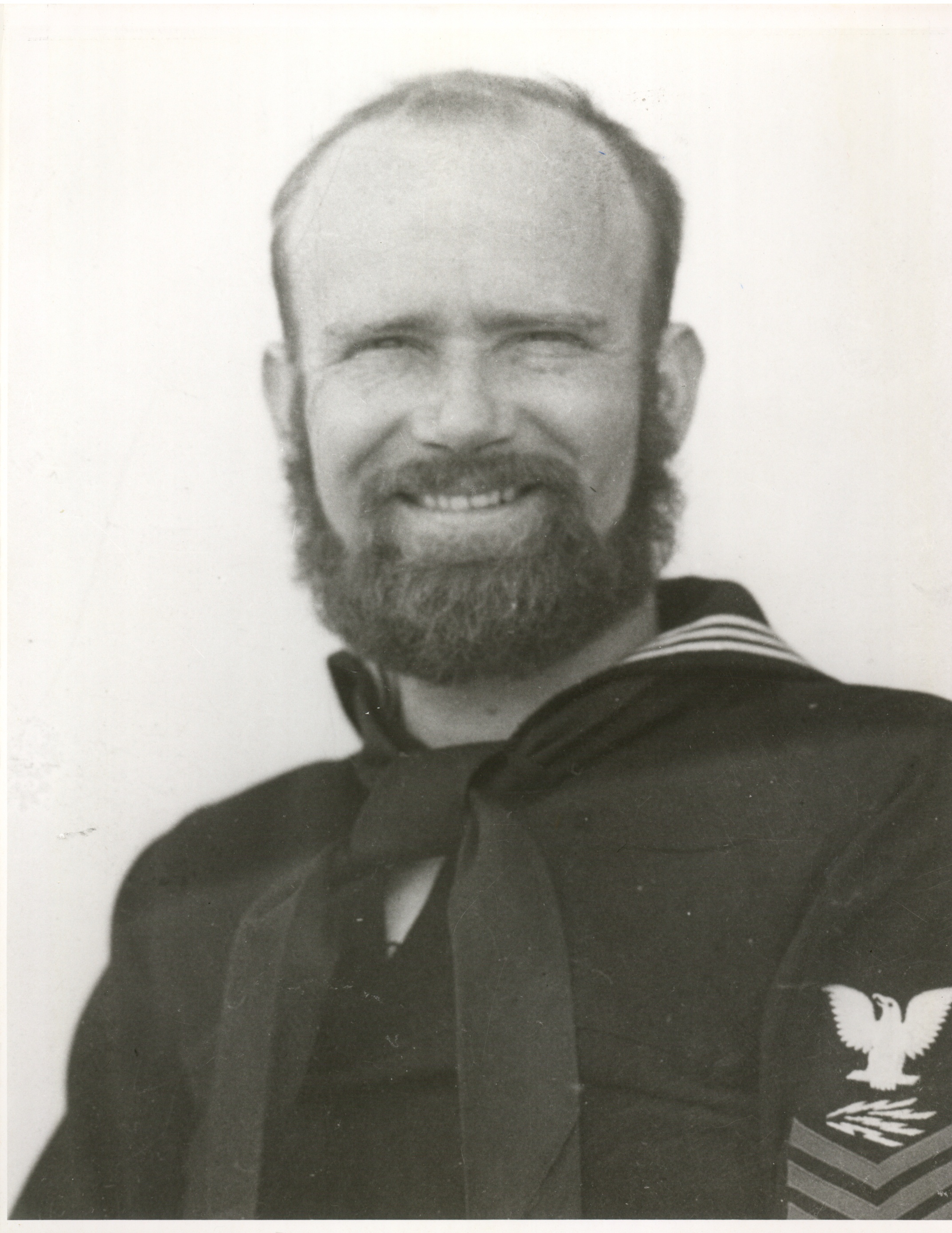

John A. Pritchard of the USCG Benjamin A. Bottoms of the USCG Loren Howarth of the US Army

In 1942 the United States had just entered World War 2 and was rushing to send equipment and supplies to European allies. Aircraft of the era lacked the range to fly directly across the Atlantic so they made the trip to England’s airfields by linking shorter hops via the arctic. The unpredictable weather and conditions over Greenland caused many plane crashes and in November of that year an amazing series of events unfolded.

A B-17 bomber that had been diverted to search for a missing cargo plane hurtled into the glacier during a white-out. Unbelievably all crew survived and radioed for help. A pair of bold young aviators operating a U.S. Coast Guard amphibious biplane that was stationed aboard a ship patrolling eastern Greenland located the B-17 and hatched an audacious plan to rescue the men. They landed on the glacier to pluck injured crew from the ice and flew them back to the Coast Guard cutter. On their second flight back to the ship a storm moved in, the pilot became disoriented, and the plane vanished in the swirling snows. The story of the brave Americans involved in this gripping adventure is told in captivating detail by Mitchell Zuckoff in his New York Times bestseller, Frozen in Time.

The missing men were pilot Lt. John Pritchard, radioman Benjamin Bottoms, and U.S. Army Air Corps Cpl. Loren Howarth. They made the ultimate sacrifice in their attempt to rescue their fellow Americans. Although they have never been found, their memory lives on and several attempts have been made to locate them.

In 2010 a search mission went out to search for possible crash sites. This trip, jointly led by Coast Guard and a private firm, was hampered by inclement weather. In 2012 another private search, again supported by the Coast Guard, encountered better weather and succeeded in identifying wreckage from the plane at a depth of 40 feet in the ice. A return mission in 2013, this time led by the Department of Defense Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command (JPAC), sought to recover the men but was unable to locate the remainder of the plane. In 2014 JPAC successfully tested custom-built equipment that would reach the men beneath the ice but left without finding the crash site.

Global Exploration and Recovery recognizes the important investments our Coast Guard and JPAC have made in the broader effort to bring home Pritchard, Bottoms, and Howarth. Our goal is to advance the mission of repatriating these men to their families by focusing on finding the plane. We believe the first priority is discovering the plane’s exact location in order to lay the groundwork for a full-scale recovery mission. We plan to conduct this search in an efficient and flexible manner with proven tools and techniques.

What we’ve accomplished:

1.

2.

2016: Our team traveled to Greenland in the summer of 2016 and was able to successfully test new research techniques and mission methods, and prove the capability of our light and swift approach - achievements critical to all of our future work.

2018: Our team traveled to Greenland in the summer of 2018 and covered more ground in our radar survey than in all previous missions combined. To accomplish this we found new ways to be efficient and took advantage of the team’s strengths. The team also focused its survey on an area of the glacier that is consistent with historical records of where the plane crashed and how it might have moved over time in the shifting ice. No prior missions investigated the vicinity where GEaR discovered the anomaly. Analysis of radar data suggests that the anomaly is the same size as the missing plane, is at a depth within the expected range, and is not a natural feature like an air pocket, rock, or crevasse.